CANSLIM Star Trader: An Interview with Gil Morales, Part 2By David Penn June 6, 2008

In the Part 1 of our conversation with Gil Morales (

http://www.GilmoReport.com), protégé of the legendary William O'Neil and principal of Gil Morales & Company, we talked about some of his early influences - traders like Nicholas Darvas, Richard Wykcoff and Jesse Livermore - as well as what he calls the

Big Stock Principle of investing in and trading around the truly important stocks that mutual funds and institutions "have to own." As Morales described the concept of Big Stocks:

"It's this concept of

what is driving the economy right now.

Which companies are at the forefront? Which companies are at the

cutting edge? Which companies are

the big innovators within the economy?"

In this, the second half of our interview with Gil Morales, we take a closer look at some of his trading and investing principles through the lens of trades he has made, both recent and historical. How long does he hold these Big Stocks? How does he know when to get out? And how much attention does he pay to the so-called "big picture" of the economy and the major market indexes? Find out here in part 2 of "CANSLIM Star Trader: An Interview with Gil Morales."

David Penn: When you're talking about these sorts of stocks, these big name stocks, the stocks with these five-year track records of running growth,

what's the holding period?Gil Morales: If it doesn't do what you want it to do, we would generally have a stop loss at 7 percent. My stop losses tend to be a little faster than that simply because I feel that I should be buying them right. At this point I should be good enough at picking stocks that

when I am buying them they should be very close to an infliction point. At least a point where they're going to start to move for me.So if I buy a stock and

if after a week, say, it's not doing anything for me, and I have something else that is actually working for me, then I get into what O'Neil calls "force feeding." That's when you pull money out of that stock that isn't doing anything - which is dead money - and you move it into things that are starting to move. So it could be a matter of a few days if something isn't working for me.

In terms of holding for a move, as long as the stock acts properly and it remains healthy, I'll hold a stock. Now from a practical standpoint I probably, in general,

hold stocks six to 12 months. Just going by what my practical experience has been.

Now

I'll trade around core positions. And I will

cut back or even sell a position if I think the market's going into a correction and the stock has run up to a point where I think it's going to have to form another base or another consolidation. Then I'll wait for it to set up within that consolidation and flash to another buy point. And I'll re-enter when I think the general market has sort of righted itself once again.

So an example would be Apple in early 2005. The stock had a great move in '04 and I was holding a million shares. I think it was around $44 back then before all the splits. But it did correct pretty well. Then it turned around and set up and came back in July, I think, and broke out again. And so you could come back to the stock.

But you can see if you were looking at a chart you would notice that it was in a flat base, about a six-week flat base in February through April of '05, and then it failed. And then I noticed it start to fail and I started bailing out right around 42, then 40, 39 and got rid of the whole position, a million shares.

And then it broke down to about 33 and set up again. The stock broke out again right at about 37 or 38 so I re-entered the position right there. I'm not worried about capital gains or anything like that.

What I'm more worried about is capital preservation. When you're running a 50 percent position in Apple that's a million shares, you can't afford to really sit there and let it whack you.

Penn: Right.

Morales: So the idea is we're very fluid in terms of being able to re-enter stock. We're never shy about getting rid of them when we think that they may have topped. If you go back and look at Apple in January of '06, it went into a little climactic sort of top in the 86 area and that would have been an area probably to sell because it had a pretty big move.

Now there's one other time when we'll sell stocks and that is if the stock comes out of a consolidation or a base or a box, whatever you want to call it.

And it runs up 20 percent in more than three weeks. So maybe it takes five, six, seven, eight weeks to run up 20 percent. We take the profit. And then we'll sit back and we'll see what the stock does because what we notice is that most stocks will run up 20 percent or so and then form a second base.

Now there's this old William O'Neil rule that if a stock runs up 20 percent or more in one, two or three weeks then you have to hold the stock six to eight weeks. However, to be honest, that's not something that really proves out if you look at it statistically.

Stocks that go up 20 percent in one, two or three weeks-they can pull right back.Penn: Getting back to Livermore, you mentioned the idea that when stocks are going up you want to be long. When they're going down you want to be short. What sort of tools do you use to make those determinations of whether or not we're in a bull or a bear? A lot of people said we were in a bull market starting in last fall for example.

How do you decide where we are?Morales:

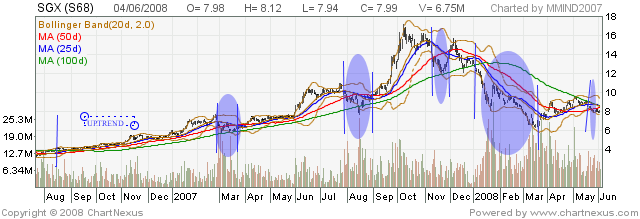

Basically by the action of my stocks. I watch my stocks primarily. The indexes are a primary indicator but also a secondary indicator to some extent, in terms of portfolio management. A good example of this is that I was long a lot in one sector in mid-October and those stocks actually acted very well as the market was correcting going into the end of October.

And I should have sat with them based on the action of the stocks alone.A lot of times stocks will continue to move higher even as the market is starting to correct and top. And you really

shouldn't blow these positions out until you start to see them break down as well because a lot of times stocks will hold up very tight and move higher. Look at stocks like Apple running right into their peaks right at the end of the year. We had already supposedly topped in October/November.

So for me, understanding whether the market is in a bull or a bear trend is sort of a function of general market indexes where you see the classic O'Neil distribution. But you're

also seeing a breakdown in the leaders. The leaders start to break one right after another.You may own a couple of them, but we were taught by O'Neil not to sell them until you start to see them break down. For all you know the market's topping - and you have three or four or five days where the index is sold off on heavier volume. Or it's telling you you're getting some distribution on stuff but you don't know if you're going into a 5 percent correction, a 10 percent correction or a 25 percent correction.

So he always told us

first and foremost watch your stocks. When your stocks tell you to get out, then you get out.

You exit the stocks. But you don't sit there and look at the general market and go: "Oh, my God. The general market's showing four days of distribution but my stock keeps going higher and I'm going to sell it now and miss out on this last 15 percent to the upside."

You watch the stocks and so there's a combination of the two in tandem when you're determining whether you're coming to the top.

Penn: What about the short side?

Morales: Obviously I'm long in a bull market and I'm short in a bear market: Once I can figure out what the longer term trend is. And sometimes even the short-term trend.

I was short coming into January and did pretty well in January but February and March were more difficult because we had such an active Fed which was a little bit unusual. I don't know when you have the market top when you have the Fed coming out every day with a 100 base point interest rate cut or some plan that they're going to do and the market's suddenly jacking up 30 points on the futures before you even get up in the morning.

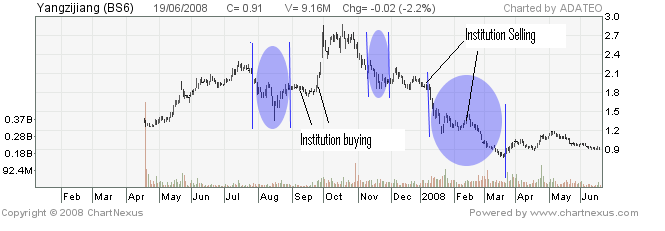

But one thing I'll look at in a bear market as an indicator are

short sale setups. And these are the

head-and-shoulders types of patterns and basically they start out where a stock breaks off of its peak very hard. This generally will form the right side of the head. You can actually see that in Apple if you look at it.

So I'm looking for those sorts of breaks and if I see those, you'll see one, two, three and they'll start to pile up. And you may still be in a bull market where some stocks are still acting OK. But those breaks certainly tell you that you're going into a weak market phase.

For example, earlier in '07 the financials all topped. The homebuilding stocks had already been getting crushed. And those are probably early warning signals that we were going to top but you really can't use them as a timing tool

until you reach a critical mass of these sorts of setups and that all started to occur in, say, December. Which sort of led you to believe that we were going to top at that time, which we did.

And you're seeing faulty bases. For instance, Apple. Those were faulty bases going into the end of December. I call them

late-stage base failure setups. So there are two setups I use - a head-and-shoulders setup and a late-stage base failure. And the late-stage base failure is generally a

base that is very short or very odd-shaped or shows a lot of wide, erratic price behavior in it. Maybe heavier volume selling within the little base. And you can see this in Apple on a weekly chart, for example. Are you looking at charts by the way?

Penn: Yes. I am actually.

Morales: If you look at Apple, you see that it came out and then it tried to break out and form this little cup-and-handle type thing on a weekly chart. And then it failed. And you can actually short that pattern right there. And when you start to see that happen, you know you're in trouble. Now you know the market's in trouble.

Now the converse is used in a bear market. During a bear market I'm looking for positive patterns. So I may be short a few things if in fact the market environment is such that I can make money on shorts.

It's very difficult to make money on the short side, by the way, and it's not something that I advocate as something you want to throw yourself into if you're new at it.

It's very difficult even for someone like me and I have had periods where I made a lot of money shorting and periods where I've made none or started to make some money and then given it all back as I have this year-so far. But no big deal; that happens.

Penn: Sure.

Morales: It's a function of the active Fed. But when you're in a bear market you start to look for bases setting up in a constructive way. I can remember one example very clearly in early 1995, when the Fed had been raising rates. Were you around back then in '94/'95?

Penn: Yes, as a matter of fact..

Morales: And you remember in February of 1994 the Fed raised rates for the first time and the bond market crashed? And then we went to the stealth bear market of '94 where a lot of stocks got hammered, but the indexes, after breaking down in February, never really went to their lows again.

Penn: Right.

Morales: Then you got into late '94 and you actually had a follow through. I think it was around December 18 1994, and stocks like Cisco started to move up off their bottoms. And by February there was all this fear the Fed was going to raise rates, and they did raise rates 50 basis points , but the market took off and we started a new bull market. And I remember at that time a lot of people were fearful and there was a lot of consternation: "Oh, my God. The Fed's going to raise rates 50 basis points and they're going to kill the market." But what I saw

there were a lot of cup-and-handle formations everywhere I looked.You could go through chart books. Back then I used to but now I go through WONDA, the excellent William O'Neil Direct Access system. And I go to the charts there and I can see what's going on in terms of what sorts of basis are setting up. Whether there are a preponderance of these setups in any given environment. And they'll give you a clue that wait a minute, this market is actually setting up to move higher.

And in late 2002, early 2003, a lot of people were still very bearish and the big mantra was that economic fundamentals don't justify a bull market. Forget that.

Economic fundamentals are not a leading indicator. They're a lagging indicator and the stock market's a leading indicator and we were starting to see a lot of bases setting up. And it even included stocks like Amazon and Yahoo which came on and had some pretty decent moves in 2003.

I know Bill was buying eBay up in November of 2002 like mad and if you go back and look at a weekly chart of eBay back then it was forming a very nice tight base and it was a leading stock. And it was telling you, if you were seeing all this just like in '95, that this market is actually more constructive underneath the surface than it appears. Much more than, say, the news would lead you to believe. And even much more than the pundits and the analysts would lead you to believe.

But I'll tell you, I actually think that you're better off

being bullish most of the time because you make more money on the bull side. When the market turns if you have too much of a bearish mentality - and I'll suffer from this sometimes - you won't see it right away. It'll take you a little bit of time. And if you're bullish most of the time your orientation is that way. You'll pick things up a lot faster.

Penn: Do you have any sense of what is it, what's the trap that catches traders who get in - I don't mean to impugn someone who successfully short sells or even does that for a living -but for those who become a little bit too wedded to that bearish approach to stock. Do you have any idea what it is that sort of trips in the mind that makes it hard for people to sometimes get out of that bearishness? Is it just fear?

Morales: I think it is fear but I think it's also once people get into a way of thinking it becomes

"what is the line of least resistance," and you get yourself into a negative frame of mind. It's easy to go that way. I think it's very typical of the period of 2000 and 2002-things were lousy for two whole years.

And starting now is the longest bear market that many have ever seen-well, it is for me and for you as well if you're under, say, 55, 60. You didn't go through '73/'74-that whole period.

It's the longest bear market we've ever seen, and I think it just sort of beats people down so they just no longer can see things in a positive light.

To me, that was Bill O'Neil's great incredible strength. Let's think about this. This guy grew up in the Depression. He started trading, I think, when he got back from the Air Force, which I think was in early '50s or late '40s. And so he's seen everything, bad and good. And yet he's still able to maintain this sort of relentless optimistic force that allows him to see things clearly.

I think that's really the key.

You don't allow your mind to get into a rut one way or another. And I think Bill is great at keeping things fresh in his head and also eager to find the next opportunity.

It's all about "how much you made when you were right" & "how little you lost when you were wrong"

**

** **

** @@

@@